About the Work

During World War I, Kirchner came to regard the fairy-tale like story “Peter Schlemihls wundersame Geschichte” (“Peter Schlemihl’s Miraculous Story”;1813) by Adelbert von Chamisso (1781–1838) as a parable of his own loss of identity. He executed the “Schlemihl” cycle – his boldly autobiographical interpretation of the tale – the same year he was released from the military. The deeply self-reflective nature of the series may account for the fact that he printed only five complete copies of it and distributed them exclusively to close friends.

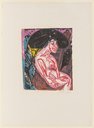

Kirchner’s “Peter Schlemihl” cycle is one of the masterworks of Expressionism. As was the case with “Cocotte on the Street” (Städel Museum, inv. no. 65598), the artist printed the six sheets from two wooden blocks each, in part sawn in pieces and usually coloured with a brush in the manner of a monotype. Closely mirroring the contents of the story, the colour zones depart more and more from the outlines of the drawing block until the composition is composed entirely of colour. In the last print, the shadow has a shape more solid than that of Schlemihl, who has begun to dissolve.

In Chamisso’s tale, Schlemihl exchanges his shadow for inexhaustible wealth, but as a result becomes an outsider to society. Kirchner read the tale as that of a “persecution paranoiac” who sells his “innermost attribute”, his shadow. He falls in love, but his love remains unfulfilled and he is moreover ostracized from society. On a country road, Schlemihl encounters the little grey man to whom he has once sold his shadow, but the transaction can no longer be undone. Downcast, Schlemihl wanders the countryside and unexpectedly meets his shadow, but does not succeed in fixing it to his soles again. In the end, Chamisso has his protagonist roaming the world in seven-league boots – a conciliatory motif Kirchner was incapable of visualizing.

About the Acquisition

From 1900 onwards, the Frankfurt chemist and industrialist Carl Hagemann (1867‒1940) assembled one of the most important private collections of modern art. It included numerous paintings, drawings, watercolours and prints, especially by members of the artist group “Die Brücke”. After Carl Hagemann died in an accident during the Second World War, the then Städel director Ernst Holzinger arranged for Hagemann’s heirs to evacuate his collection with the museum’s collection. In gratitude, the family donated almost all of the works on paper to the Städel Museum in 1948. Further donations and permanent loans as well as purchases of paintings and watercolours from the Hagemann estate helped to compensate for the losses the museum had suffered in 1937 as part of the Nazi’s “Degenerate Art” campaign. Today, the Hagemann Collection forms the core of the Städel museum’s Expressionist collection.